Who Deserves the ENCODE Nobel Prize? Ans. Ron Davis

ENCODE made the major discovery of finding 80% of human genome functional. Usually when Nobel (or IgNobel) prizes are awarded, the committees work hard to make sure other less well-known papers making similar discoveries get credited.

We looked extensively into literature to find which group made this fundamental discovery prior to ENCODE and came across work from a humble researcher from Stanford, who never bothers to read or question paper submitted under his name (for more on that see below). Please check the line marked in bold in this paper published in 2006, which was one year before ENCODE published their first paper.

There is abundant transcription from eukaryotic genomes unaccounted for by protein coding genes. A high-resolution genome-wide survey of transcription in a well annotated genome will help relate transcriptional complexity to function. By quantifying RNA expression on both strands of the complete genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a high-density oligonucleotide tiling array, this study identifies the boundary, structure, and level of coding and noncoding transcripts. A total of 85% of the genome is expressed in rich media. Apart from expected transcripts, we found operon-like transcripts, transcripts from neighboring genes not separated by intergenic regions, and genes with complex transcriptional architecture where different parts of the same gene are expressed at different levels. We mapped the positions of 3? and 5? UTRs of coding genes and identified hundreds of RNA transcripts distinct from annotated genes. These nonannotated transcripts, on average, have lower sequence conservation and lower rates of deletion phenotype than protein coding genes. Many other transcripts overlap known genes in antisense orientation, and for these pairs global correlations were discovered: UTR lengths correlated with gene function, localization, and requirements for regulation; antisense transcripts overlapped 3 UTRs more than 5 UTRs; UTRs with overlapping antisense tended to be longer; and the presence of antisense associated with gene function. These findings may suggest a regulatory role of antisense transcription in S. cerevisiae. Moreover, the data show that even this well studied genome has transcriptional complexity far beyond current annotation.

Apparently, Karma caught up to Ron Davis, because the latest Science paper with his name is getting a touch of post peer review. Derek Lowe wrote -

A reader sent along a puzzled note about this paper that’s out in Science. It’s from a large multicenter team (at least nine departments across the US, Canada, and Europe), and it’s an ambitious effort to profile 3250 small molecules in a broad chemogenomics screen in yeast. This set was selected from an earlier 50,000 compounds, since these realiably inhibited the growth of wild-type yeast. They’re looking for what they call “chemogenomic fitness signatures”, which are derived from screening first against 1100 heterozygous yeast strains, one gene deletion per, representing the yeast essential genome. Then there’s a second round of screening against 4800 homozygous deletions strain of non-essential genes, to look for related pathways, compensation, and so on.

All in all, they identified 317 compounds that appear to perturb 121 genes, and many of these annotations are new. Overall, the responses tended to cluster in related groups, and the paper goes into detail about these signatures (and about the outliers, which are naturally interested for their own reasons). Broad pathway effects like mitrochondrial stress show up pretty clearly, for example. And unfortunately, that’s all I’m going to say for now about the biology, because we need to talk about the chemistry in this paper. It isn’t good.

As my correspondent (a chemist himself) mentions, a close look at Figure 2 of the paper raises some real questions. Take a look at that cyclohexadiene enamine - can that really be drawn correctly, or isn’t it just N-phenylbenzylamine? The problem is, that compound (drawn correctly) shows up elsewhere in Figure 2, hitting a completely different pathway. These two tautomers are not going to have different biological effects, partly because the first one would exist for about two molecular vibrations before it converted to the second. But how could both of them appear on the same figure?

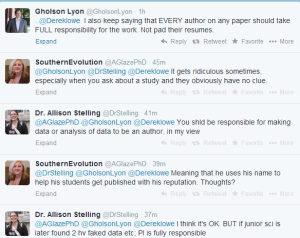

Needless to say, Twitterosphere is very angry today.