A Road Map for our Journey through the Transcriptomic Maze

It has not escaped our mind that, in our writing so far, we did not explain what we intend to achieve here. Today we will take a brief pause from scientific topics to reflect on our limited goals.

As you are well aware, biology changed rapidly over the last few decades, and the pace of change seems to be accelerating in recent years. Sequencing and assembly of human genome, hailed as one of the greatest achievements of mankind, was done at a staggering cost of ~$3B and the project needed decade long collaboration of the brightest minds in the world. Today, only ten short years later, a small group of researchers with limited funds can think of assembling a comparable- sized genome.

This change has been brought forth by technological progress on two fronts. Firstly, new innovations in chemistry and semiconductor processing continue to drive down the costs of sequencing, arraying and other large-scale biochemical experiments. Secondly, an equally fast-paced set of innovations in the computational arena allows proper utilization of data derived from large-scale experiments. For example, it would not have been possible to quickly align billions of short reads to a reference genome, if algorithms incorporating Burrows Wheeler transform were not developed for bioinformatics. Similarly, using innovative graph- theoretic concepts, such as de Bruijn graphs, de novo assembly of genomes from short reads has become possible.

We are a noticing a partition among the bioinformatics community regarding development and use of various high-performance algorithms. One group includes algorithm/code developers, who understand the inner details of their programs and other comparable approaches. The other group, involving vast majority of users, only learn the commands for running those programs, but pay less attention to detailed algorithms applied in solving the problems. There is nothing inherently wrong with this mode of operation. While driving, I rarely think about what an amazing engineering feat my car’s design is and instead worry about the swerving driver in the next lane. Most popular bioinformatics programs run readily out of the box, and there is no need to go through lines of incomprehensible codes to get a task done.

For cutting edge research, however, understanding algorithms at a broad level provides many benefits. Bioinformaticians live on the edge with available computational resources and are always in the lookout for the most powerful machines available in the universe. By knowing how different programs are operating, they may be able to partition or filter the input data in intelligent ways and do more with the same computing resources. Secondly, knowledge of intricacies of programs would help them in critical decisions, such as i) whether to buy a new high-RAM computer or buy a cluster, or to use commercial cloud facilities, ii) how much memory and disk-space are needed to work with a particular data set, iii) understanding the trade offs made by some programs that run slowly, but require less memory, etc.

In this blog, we will explain various computational approaches and algorithms in the simplest manner. Traditionally, this role is fulfilled by books written by experts after a field matures enough. However, in the fast-paced world of bioinformatics, the gap between discovery of a new approach and publication of books is too large for the presented approach to remain useful.

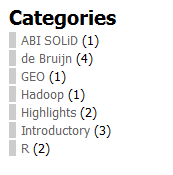

The discussions here will focus on transcriptome analysis, but many of the approaches are equally applicable for genomic data. Regarding style, you may have noticed that we cover a wide spectrum of topics, among which only a few may interest you. Please use the categories links on the left sidebar and tags at the bottom of the posts to find topics of your interest. Articles that would interest nobody except us are placed in the ‘editorial’ category.

One last word - if we do not post from time to time, please do not take that as an indication that the bio-world has stopped innovating, and we find nothing to write about. It is more likely that the pace of innovation has turned too fast for us to catch up. God forbid, if our writing stops completely. We may have met the fate of brilliant physicist Paul Ehrenfest, who, in another fast-paced era, decided to leave the world, being unable to catch up with the latest discoveries in quantum mechanics.