Notes on Jay Shendure's Seattle Meetup Presentation

Few days back, we posted a short commentary on Jay Shendure’s talk at Seattle Sequencing Meetup. Today we have some time to post the notes taken from the presentation. They are no substitute for attending his presentation, and we wish we could find a video from youtube or elsewhere.

There are several reasons we are taking the trouble to post detailed notes from his talk -

(i) Jay is an MD as well as among the leading scientists working on next-gen sequencing. So, he chose very neat NGS experiments with clinical use in mind. So, at the least, his talk gives doctors some ideas about where these new technologies fit in the big picture. Remember this discussion?

(ii) Jay started as an assistant professor in 2008 right when NGS was coming up, but did not have millions of dollars at his disposal for elaborate NGS experiments. So, being from George Church’s lab, he understood that NGS would revolutionize biology and medicine, yet he could not chase every possible medical application. The thoughts given by him to find best value for money may help others in the same situation.

For the sake of discussion, we will cut and paste few slides below, but you can go through all slides together here.

-———————————

Part 1. (slides 1-5)

Jay splits the types of work his lab does into following categories - i) Genetics, ii) Function, ii) Synthetics, iv) Tagging, v) Contiguity, vi) Translation. For details on what they mean, please check his research homepage dedicated to Krishna (why??).

-———————————-

Part 2. (slides 6-7)

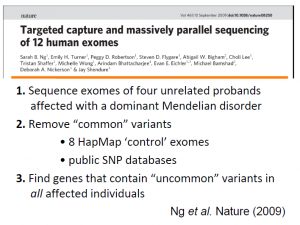

Going back to 2008, Jay understood the potential of NGS, yet the cost of full human genome sequencing was $250K/person, and doing the same for replicate experiments to make clinical conclusions would have cost millions of dollars. So, (i) he simplified his task by sequencing only exome regions, which constitute 1% of genome, (ii) he picked Mendelian disorders marked in red on slide 7.

-———————————–

**Part 3. (slides 8-24) - Mendelian disorders **

Mendelian disorders are rare single gene diseases. Although each Mendelian disorder affects very small number of people, collectively they affect 1% of the human population (according to Jay, but wish to get a citation). Origins of about 2,000 Mendelians genetic disorders are solved and about 2000 are unsolved.

To solve them, one needs to sequence the exomes of parents and children with the disorder, and then compare those sequences. The full workflow is given in slide 10 and an example is worked out in slide 11, where a previously known gene MYH3 responsible for ?? (do not remember) was correctly identified.

Shendure’s group used the same idea for Miller syndrome and linked DHODH (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase) with the diseases. After they found out the gene, other phenotypes for the disease, such as lung phenotype, made sense.

However, all cases were not so easy. When they worked on Kabuki syndrome, their standard workflow came up with incorrect result MUC16. They relaxed their workflow to allow for some misses (5 out of 10 instead of 10 out of 10), and found the correct gene MLL2 (trithorax-group histone methyltransferase).

Interestingly, Shendure’s group observed that Kabuki syndrome was caused by de novo mutation in child, and could not be identified by mapping only. For more details, please follow papers by Ng et al. 2010 and their website http://www.mendelian.org.

-———————

Part 4. (Slides 25-36) - Autism Spectrum Disorder

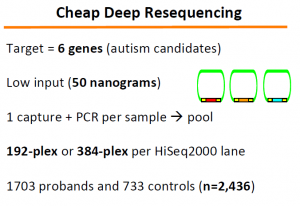

Next, Jay’s lab extended the above concepts to look for genetic origin of autism. The problem here is extremely difficult. They could explain 0.5% of autism, which Jay explained as remarkable success given how complex the disease likely is.

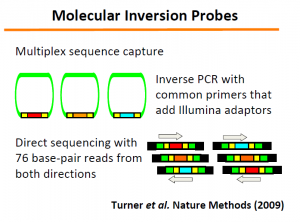

The ‘Molecular Inversion Probes’ technology (slide 33-34) developed in this regard can be very useful for other purposes.

The relevant papers are -

and

Multiplex amplification of large sets of human exons Porreca et al. Nat Methods 2007

-—————–

Part 5. (Slides 37-47) Genome Sequencing, Resequencing, Phasing and Completion

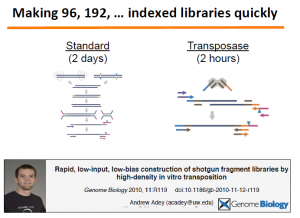

We will fill up this section later. Essentially, they used fosmids to identify phases of the genome of an Indian (Gujarati) person. The most important part is in the technology they developed for rapid library creation.

Relevant paper is here -

Rapid, low-input, low-bias construction of shotgun fragment libraries by high-density in vitro transposition Adey et al. Genome Biology 2010, impact factor 9.04723. The paper was mentioned in our earlier commentary on nextera kit.

-———————–

Part 6. (Slides 48-64) Reconstructing Fetal Genome

Can we reconstruct the genome of a baby WELL BEFORE she is born? That was the question asked by Shendure’s lab, because it could help replacing various less accurate non-invasive and invasive genetic tests with more accurate tests. The help came from an old 1997 paper by Chiu et al., which showed that ~5-15% in plasma were of fetal origin, and most of fetal genome was represented.

Children’s chromosomes are near exact copies of parents’ chromosomes. More specifically, when one compares every single site of a child’s chromosome with the same of her parents’, there are three possibilities -

(i) the site is homozygous between parents and carries directly to child,

(ii) the site is homozygous between parents, but has de novo mutation in child,

(iii) the site is heterozygous between parents.

The third case is the most difficult, and Shendure’s lab came up with a nice statistical method to sort out nucleotides in fetal chromosomes (slide 57-58). It needed using haplotype information and hidden Markov model.