New Kind of Science

How will humans occupying the earth 1,000 years later judge our era? Will they find our perception of complexity in human genome a bi-product of our math being too simple? In our earlier commentary titled “How Basic Math Limits Scientific Discoveries”, we discussed the evolution of mathematics over the last 2,500 years. Greeks and Romans perceived many things around them to be complex, simply because their mathematics did not have a way to describe them. Multiplying two numbers was complicated (shortcoming of Roman number system) and so was describing the diagonal of a rectangular triangle (Greek’s did not believe in irrational numbers). Mathematicians have overcome those handicaps since then. The field has grown rapidly since the Age of Enlightenment and gave modern scientists many tools to explain their observations. Maybe our mathematical paradigm is complete and we have nothing to worry about.

Before we speculate about the next 1,000 years, here is a quick diversion. Our six year old son was bored and I decided to play a new game with him. We already played with imaginary numbers and stopped after connecting geometry and number systems (contribution of Caspar Wessel). I do not want to push too much in that direction beyond what a kid can easily absorb.

He loves LEGOs and so I asked him to form a pattern following a set of rules. On the top-most row of the board, only one spot was filled. Then he was asked to fill up the next few rows using these rules.

i) In general, if a spot is filled, the spot below it will be filled. If a spot is empty, the spot below it will be empty. There are only two exceptions.

ii) Exception 1. If a spot is filled and both its left and right neighbors are filled, the spot below will be empty.

iii) Exception 2. If a spot is empty, but its right spot is filled, the spot below will be filled.

We proceeded for a few rows and here is what he came up with before we ran out of small pieces.

Knowledgeable readers will possibly recognize the pattern. If we had plenty of LEGOs, we could reconstruct the image in the cover of Stephen Wolfram’s book titled ‘A New Kind of Science’.

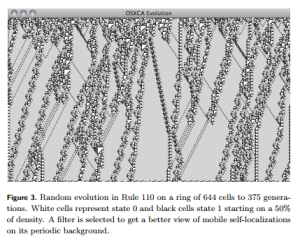

The rules we followed to form the LEGO pattern were described as ‘rule 110’ in Wolfram’s book, and we already alluded to it in our earlier commentary titled “Fractals and Scale-free Networks”. Here is what you expect after continuing further. We reconstructed a very tiny part of the top corner of following figure with LEGOs, but you can see early emergence of fractals in the LEGO structure.

Why do we keep talking about it all the time? What relevance does that pattern have with biology and bioinformatics? Let us explain.

1. Fractals are Everywhere in Nature

We observe various degrees of fractal behavior in all natural systems. You see them not only in the shapes of the trees or leaves, but also in the evolutionary trees of protein families, protein-protein interaction networks, sizes of businesses and social organizations, sizes of countries, and so on. Based on that, you expect all our elementary textbooks to be filled with analysis of fractals, but they are not. Our mathematical tradition starting from Greek geometry relies on straight lines, squares and circles, because the Greeks found those shapes easy to analyze and build. All our mathematical tools - linear algebra, linear differential equation, linear partial differential equation, etc. suffer from that drawback. Should we let our mathematics to describe what is most frequently observed in nature, or should we deal with the problems that can be handled easily, irrespective of practical relevance? So far, the later seems to be case.

2. Cellular Automata Method is Simple and Complete

One earlier challenge of presenting fractals within our existing mathematical framework was that they were very difficult to derive. Someone needs to learn about linear differential equations and then venture into nonlinear equations to get anywhere close. That is one reason for the Greeks, Hindus, Islamists, Venetians or the Westerners not to come across the structure in their 2500 years of mathematical development.

With Wolfram’s method, even a little kid can get to them with no trouble starting from simple rules. That is quite fascinating.

For those, who like to play with the structure further, here is a quick PERL code. There is nothing fancy and you can write something similar in another language in a rather short time.

`

initial condition (all white, only one black)

for($j=-100; $j<=60; $j++) { $a{“1 $j”}=”.”; }

$a{“1 11”}=”B”;

print first line

for($j=-100; $j<=60; $j++) { print $a{“1 $j”}; }

print “\n”;

implement rule for each line up to 18 lines and print

for($i=2; $i<100; $i++)

{

for($j=-100; $j<=60; $j++)

{

$x=$i-1; $jm=$j-1; $jp=$j+1;

default rule: carry one line into next line

$a{“$i $j”}=$a{“$x $j”};

if three consecutive spots are black, the middle of next line will be white

if(($a{“$x $j”} eq ‘B’) && ($a{“$x $jm”} eq ‘B’) && ($a{“$x $jp”} eq ‘B’))

{

$a{“$i $j”}=’.’;

}

if white spot has black on right, the white turns into black

if(($a{“$x $j”}eq ‘.’) && ($a{“$x $jp”} eq ‘B’)) { $a{“$i $j”}=’B’; }

print $a{“$i $j”};

}

print “\n”;

}

`

Mathematical completeness is another attractive feature of Wolfram’s presentation. Overall, you can cover the entire spectrum of elementary cellular automata (CA) with only 256 rules (2^8) and rule 110 is one of them. That is important, because we want to ensure that our mathematical tools have some degree of completeness before using them to describe wide array of physical observations.

2. Complexity Can Come from Simplicity

If you observe the evolution of the LEGO pattern, you will see the it started with one filled spot and three very simple rules. Yet, it formed highly complex patterns after several iterations. That means we do not always have to throw our hands up and order more sequencing (1000 genome project, 1 million genome project, etc.), when we find certain biological observations too hard to define with our current data. Our observed complexity can be an outcome of limitation of our elementary mathematical tools.

Formation of soliton waves was one feature of that complexity. Solitons had been very hard to describe using our traditional mathematical framework and readers can go through Fermi-Pasta- Ulam problem and Kortewegde Vries equation to see their historical development. It is definitely not child’s play. In contrast, you can derive soliton-like waves and their collisions fairly easily from rule 110. As an example, please take a look at the following image borrowed from a recent arxiv paper (“On soliton collisions between localizations in complex ECA: Rules 54 and 110 and beyond”).

3. Turing Machine

Computer scientists will find it fascinating that rule 110 is Turing complete or computationally universal, and likely the simplest set of rules to have such property. That means the system can be used to do any single-taped Turing machine.

In computability theory, a system of data-manipulation rules (such as a computer’s instruction set, a programming language, or a cellular automaton) is said to be Turing complete or computationally universal if it can be used to simulate any single-taped Turing machine. A classic example is lambda calculus. The concept is named after Alan Turing.

Computability theory includes the closely related concept of Turing equivalence. Two computers P and Q are called Turing equivalent if P can simulate Q and Q can simulate P. Thus, a Turing-complete system is one that can simulate a Turing machine; and, per the ChurchTuring thesis, that any real-world computer can be simulated by a Turing machine, it is Turing equivalent to a Turing machine.

In colloquial usage, the terms “Turing complete” or “Turing equivalent” are used to mean that any real-world general-purpose computer or computer language can approximately simulate any other real-world general-purpose computer or computer language. The reason this is only approximate is that within the bounds of finite memory, they are only linear bounded automaton complete. Also, any physical computing device has a finite lifespan. In contrast, a universal computer is defined as a device with a Turing complete instruction set, infinite memory, and an infinite lifespan.

Conclusion

Getting back to our original question, is our conventional mathematics (traditional geometry + number system + algebra + Newtonian calculus) complete enough to describe all kinds of complexities in nature? The answer is no, because the fractals present everywhere in nature are quite hard to derive from traditional tools.

Will Wolfram’s CA become useful to fill up the holes in near term? The answer is no again, because, as we explained in previous commentary, science is a method to describe natural observations in terms of commonly accepted mathematical language. Until all school-kids start learning about fractals and fractal-based complexity, Wolfram’s method will possibly have the same impact as Hippasus in ancient Greece.

Hippasus, however, was not lauded for his efforts: according to one legend, he made his discovery while out at sea, and was subsequently thrown overboard by his fellow Pythagoreans for having produced an element in the universe which denied thedoctrine that all phenomena in the universe can be reduced to whole numbers and their ratios.

No matter what happens in near-term, it appears quite likely that complexity theories will redefine mathematics and sciences in long-term future. We often mention Wolfram’s name, because his presentation of nonlinear systems is the simplest. However, other scientists like Murray Gell-Mann saw similar promises, when they founded Santa Fe institute to continue theoretical research on complexity. P. W. Anderson, whose essay “More is Different” was mentioned here is also actively involved with the same institute. Brilliant theoretical physicists like them are out of mainstream attention, but they and their followers continue to actively push the boundaries of mathematics and science. It is only that biologists will not adopt their discoveries until those become mainstream.

-————————–

Readers may also enjoy the following commentaries -

(on chaos theory) - How about a Chaotic Genome Assembler?

(on mathematics of ‘sand piles’) - What Does BTW Stand for?