Crossroads (ii) - Is It Too Late to Acknowledge that Systems Biology and GWAS

Emergence of high-throughput sequencing technologies got a new generation of computer scientists interested in bioinformatics. So far, they have been busy developing algorithms to rapidly process the large volume of reads into meaningful information (i.e. high quality alignments, assemblies, etc.), but those computer science aspects of the challenge have been addressed satisfactorily. In an earlier commentary ( Bioinformatics at a Crossroad Again Which Way Next? ), we posed the question of what would be the next direction for bioinformaticians.

For those who do not know, the same question was asked in early 2000s after completion of the human genome project, and two paths (GWAS and Systems Biology) were selected after rejection of many other more sensible suggestions. By now, both of those approaches failed spectacularly, with the most recent example provided by modENCODE. Please check the following commentary by Dr. Gary Ruvkun, a Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, at Dan Graur’s blog. Dr. Ruvkun shares many other opinions with our blog ( decline of US science, rise of mediocrity, decline of mainstream journals, etc.), but his primary observation is that modENCODE failed to discover anything valuable given the money spent on them.

I have enjoyed your devastating critiques of Encode and ModEncode. I forwarded your On the immortality of television sets to dozens. But you are too gentle here. I get Nature now for free, since I review quite a bit for themit is a sign of the decline of journals and the decline of the science that they publish that they now give it away to their reviewerssort of like the discounted subscriptions for magazines which sell high end merchandise if you live in the right zip code. So, I was well rested today and decided to give the 5 papers of the modEncode a chance to blow me away. Not one interesting finding. Not one. Worse than junk food, which at least satisfy in the moment. Hundreds of millions of dollars on genome scale observations of transcripts and transcription factor binding. Grind up a whole animal and look at the average of hundreds of cell types pooled together. A few weak correlations between this and that transcription factor. A few differentially spliced mRNAs. I would say that about 1% of the modEncode budget was appropriate for getting better transcript annotation, but the rest was misguided genomics. A waste of research dollars! The so-called brain trust of the NIH does not understand the difference between big science that is foreverthe thousands of genome sequences that are precise to one part in a billion and will be used for the rest of timeand big science datasets that will simply fade away because they are so imprecise and uninteresting to anyone, like RNA seq. On the other hand, the good news about projects such as these is that the hundreds of authors on those papers are distracted from serious science, and the bizarre sexiness of these papers attracts other marginal intellects to those fields, and thus fields that are important becomes much less competitive, ignoring the bloated budgets of these Soviet- style five-year plans.

In our opinion, it is time to set bioinformatics on a new course, but we need to review the previous approaches to understand why they failed.

1. History of Systems Biology

Systems biology can be more aptly described as shotgun biology and its basic premise is as follows. In this method of doing biology, high-throughput machines would collect and store large amount of somewhat noisy data from various biological systems to build “the omics databases”, and then computer scientists would come up with magical algorithms to turn noisy data into functional information.

That way of thinking started to gain acceptance after two remarkable achievements of the late 1990s - (i) Celera’s successful assembly of human genome from shotgun reads, and (ii) Google’s success in building a high quality search engine. Those successes made other think of computer scientists as God-like, who could come up with unusual algorithms to turn every low- quality and low-cost Omics databases into gold.

Instead we have only seen proliferation of ‘omics’ terms and inflated claims about the success of computer algorithms (check The network nonsense of Manolis Kellis and related posts in Lior Pachter’s blog), but hardly any real contribution was made, as Dr. Ruvkun observed.

-————————————————–

2. History of GWAS

GWAS emerged as a poor man’s way to connect ‘THE’ human genome with diseases in late 90s, when NIH was still in the process of hyping up human genome project. We covered that history in the following two commentaries.

An Opinionated History of Genome Assembly Algorithms (i)

An Opinionated History of Genome Assembly Algorithms (ii)

The public was reluctant to bear the cost of that humongous project and the project had to be sold by making claims about how it would lead to curing diseases. However, there was one problem. If genome sequencing of every human being needed another billion dollars, there was no way to back NIH’s claims of ending all human suffering by 2010. GWAS was one way to reduce the dimensionality of the problem in that ‘sequencing is expensive’ era.

In late 90s, Professor Ken Weiss correctly saw the futility of embarking on the GWAS tree (see Battle over #GWAS: Ken Weiss Edition), and he continues to write informative commentaries on related topics in his excellent The Mermaid’s Tale blog.

With cheap sequencing, the original cost constraint leading to GWAS has been removed and it is now possible to propose and consider other alternatives instead of following the failed path.

-————————————————–

4. Inherent Drawbacks of the Current Approach

Before proposing any alternative, let us first review the inherent drawbacks of approaches pursued over the last 15 years.

i) Reverse Problem is Impossible to Solve

The supporters of current paths often argue that their apparent failure is from not being able to collect enough data and they will be successful given they have 100,000 human genomes (or insert a large number) instead of 1,000 genomes. In a thought-provoking article titled ‘Sequences and Consequences’ (check Thought-provoking Article on Systems Biology from Sydney Brenner), Sydney Brenner argued why that is not the case. Systems biologists are trying to solve the inverse problem of physiology, but there is no straightforward way to solve inverse problems.

I want to show here that this approach is bound to fail, because even though the proponents seem to be unconscious of it, this claim of systems biology is that it can solve the inverse problem of physiology by deriving models of how systems work from observations of their behaviour. It is known that inverse problems can only be solved under very specific conditions. A good example of an inverse problem is the derivation of the structure of a molecule from the X-ray diffraction pattern of a crystal. This cannot be achieved because information has been lost in making the measurements. What is measured is the intensity of the reflection, which is the square of the amplitude, and since the square of a negative number is the same as that of its positive counterpart, phase information has been lost. There are three ways to deal with this. The obvious way is to measure the phase; the question then becomes well-posed and can be answered. The other is to try all combinations of phases. There are 2n possible combinations, where n is the number of reflections; this approach might be feasible where n is small but is not possible where n is in the hundreds or thousands, when we will exceed numbers like the total number of elementary particles in the Universe. The third method is to inject new a priori knowledge; this is what Watson and Crick did to find the right model. That a model is correct can be shown by solving the forward problem, that is, by calculating the diffraction pattern from the molecular structure. The universe of potential models for any complex system like the function of a cell has very large dimensions and, in the absence of any theory of the system, there is no guide to constrain the choice of model. In addition, most of the observations made by systems biologists are static snap-shots and their measurements are inaccurate; it will be impossible to generate non-trivial models of the dynamic processes within cells, especially as these occur over an enormous range of time scales from milliseconds to years. Any nonlinearity in the system will guarantee that many models will become unstable and will not match the observations. Thus, as Tarantola (2006) has pointed out in a perceptive article on inverse problems in geology, which every systems biologist should read, the best that can be done is to invalidate models (in the Popperian sense) by the observations and not use the observations to deduce models since that cannot be successfully carried out.

Readers can find professor Tarantola’s paper from his informative website, where he explained his losing faith in humanity near the end of his life possibly after failing to convince them about the futility of solving inverse problems from ‘big data’.

My technophobia.

In recent years, I have been following an unexpected path.

I started having doubts about the necessity of continuing with the development of modern technologies (cell phones, internet, virtual realities, etc.), and had fears about the long-term effects of the present technological trends (geoengineering the Earth, genetically engineering living beings, etc.).

Then, I started wondering about the value of the non-social sciences (mathematics, physics, chemistry, medicine) after the last fundamental scientific discoveries (Darwin’s theory of evolution, Pasteur’s germ theory of disease). Have the hard sciences still any interest today (besides helping to accelerate technology)? I do scientific research every day, but I am feeling increasingly guilty for doing that. At this point, I still valued the sciences that could help improve our human condition or help to protect biodiversity (the most urgent problem on Earth).

To arrive where I am now. Questioning the whole scientific entreprise. At any time in the past, I would have decided that science was good for the Sapiens. But now, with hindsight… As Francis Bacon said, knowledge is power. The problem is that we, Sapiens, are not genetically adapted to control all the power we already have. Science has empowered us too much.

After destroying much of the vegetal and animal species in the Earth, we have started destroying ourselves. Like other civilisations have destroyed themselves in the past. But this time, the collapse may be global.

What should we do? Radically change the economy, radically reverse our priorities, radically diminish the number of inhabitants in the Earth. Stop having a nave faith on the “progress” brought by science and technology. Become humble.

Distraction aside, one can make a clear case that collecting bigger and bigger databases is not going to help solve the inverse problem.

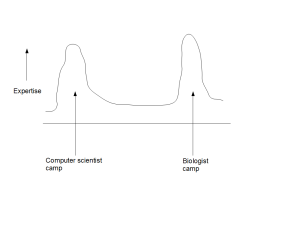

ii) Partitioning of Experts into Camps

The second drawback of contemporary approach is that it partitions the experts into multiple distinct camps. Computer scientists hang around with other computer scientists, while providing lip service to biology. Biologists are surrounded by biologists and view computer science approaches as ready-made kits.

One may argue that the partitioning will go away over time, when enough experts cross the boundaries and start to solve problems by being in the middle. Instead, we see the partitioning as an inherent flaw of the system and do not expect it to go away, until the middle is defined. As long as the computer scientists believe that they will be able to solve all biological problems from noisy data by starting from the genome and annotations, and biologists believe that they can go straight to the lab to validate the small number of ‘leads’ generated by computer scientists, there will not be enough experts in the middle. The lack of experts in the middle is due to not having a persuasive strategy to define the middle, where the members from both camps can move to achieve higher benefit. That is not possible in the current flawed way of doing biology.

iii) Linearized genomic view of Biological Information

The contemporary methods of understanding the biological systems is genome- centric. That linearized simplification is convenient for computer scientists, but can be argued as not being the biologically correct form of simplification. A linearized view gives equal weight to all parts of the genome, unless proven otherwise. However, we know that various blocks on the genome move around or get deleted with little functional changes in organisms. This ‘a priori’ knowledge needs to be incorporated into the thinking of computer scientists. At present, when those constraints are added to the informatics model, the model gets more and more complex. We clearly see the need for more hierarchical way for data reduction, and leaving the genome as starting point would be a good start.

iv) Difficult to Incorporate Evolution

In his article “Sequences and Consequences”, Brenner argued about the need to inject ‘new a priori knowledge’ to reduce dimensionality of the problem, and evolution can be argued as another source of such a priori knowledge. However, in the contemporary way of high-throughput biology, incorporating evolution often leads to adding more noise than signal. The reason for this is the lack of understanding of the relation between genome evolution and functional evolution.

v) Many Bad Claims based on Noisy Data

Sidney Brenner often presents the current approach as ‘low input, high throughput, no output’. Computer scientists have another term - ‘garbage in, garbage out’ - to describe the same problem. We are seeing proliferation of noisy data and bad claims, because shotgun biologists feel the urge to say something about biology to make their papers respectable to biologists. ENCODE is one bad example, but there are many other. Looking for positive selection using packages is one apparently easy way to connect genome with phenotypes, but in a paper published in 2009, Dan Graur and colleagues showed -

Published estimates of the proportion of positively selected genes (PSGs) in human vary over three orders of magnitude. In mammals, estimates of the proportion of PSGs cover an even wider range of values. We used 2,980 orthologous protein-coding genes from human, chimpanzee, macaque, dog, cow, rat, and mouse as well as an established phylogenetic topology to infer the fraction of PSGs in all seven terminal branches. The inferred fraction of PSGs ranged from 0.9% in human through 17.5% in macaque to 23.3% in dog. We found three factors that influence the fraction of genes that exhibit telltale signs of positive selection: the quality of the sequence, the degree of misannotation, and ambiguities in the multiple sequence alignment. The inferred fraction of PSGs in sequences that are deficient in all three criteria of coverage, annotation, and alignment is 7.2 times higher than that in genes with high trace sequencing coverage, known annotation status, and perfect alignment scores. We conclude that some estimates on the prevalence of positive Darwinian selection in the literature may be inflated and should be treated with caution.

-————————————————–

We believe the problems listed above are not flaws of individual studies, but inherent drawbacks of the contemporary approach of high-throughput shotgun biology. What is the solution? In the following commentary, we will present our proposal for a new direction for bioinformatics.