An Evolutionary Perspective on the Kinome of Malaria Parasites

A few days back, we posted a commentary titled Vaccinating with the genome: a Sisyphean task?, and a reader asked -

Sorry being ignorant. Can we profile the diseases based all the omics data integration and then find the right cure ? What prevents us from doing it ? Is it the cost, right technology or the institutions arent just interested in it.

There are three components of studying any living organism - informational aspect, the physical/chemical aspect and the evolutionary aspect. The omics data sets and especially the genome covers only the informational aspect, whereas the other two take much more work. Moreover, they often tend to be organism-specific, which means an investigator will need to spend a lot of time thinking about data, arguing about possibilities and connecting the dots. In contrast, the modern way of doing science has been to throw technology at things and expect computer to sort everything out. If not, throw more money/technology and run a bigger experiment. That has not been working with the malaria parasite.

Here is an informative blog post from The Mermaid’s Tale on the evolution of ‘malaria-protective’ alleles of G6PD gene that explains why it has become difficult to connect various evolutionary dots.

Evolution of malaria resistance: 70 years on…and on….and on

Far beyond malaria: Relationship to fundamental evolutionary questions

The idea of balanced polymorphisms played into a major theoretical argument among evolutionary biologists at the time, and sickle cell anemia became a central case in point, and a stereotypical classroom example. But the broader question was quite central to evolutionary theory. Balancing selection was, for many biologists who held a strongly selectionist version of Darwinism, the explanation for why there was so much apparently standing genetic variation in humans, but generally in all, species.

The theory had been that harmful mutations (the majority) are quickly purged, so the finding that there was widespread variation (polymorphism) in nature at gene after gene, the result of the type of genotyping possible then (based on protein variation), demanded explanation; balanced polymorphism provided it. This was countered by a largely new, opposing view called ‘non-Darwinian’ evolution, or the ‘neutral’ theory; it held that much or even most genetic variation had no effect on reproductive success, and the frequency of such variants changed over time by chance alone, that is, experience ‘genetic drift’. This seemed heretically anti-Darwinian, though that was a wrong reaction and only the most recalcitrant or rabid Darwinist today denies that much of observed genomic variation evolves basically neutrally. But many saw the frequency of variants associated with what were seen as serious recessive diseases, like PKU and Cystic Fibrosis (and others) as the result of balancing selection.

In support of the selectionist view, many variants have been found in the globin and other genes for which the frequency of one or more alleles is correlated geographically with the presence (today, at least) of endemic malaria. But there are lots of variants that might be correlated with other things geographic because the latter are themselves often correlated with population history. Thus, the correlations are often empirical but not clearly causal. Indeed, not many variants have been clearly shown experimentally or clinically actually to be functionally related to malaria resistance.

Speaking of understanding the physical/chemical aspect of components within cell, we came across this wonderful review paper on the protein kinase genes in malaria parasite. To develop proper insight, the same kind of analysis has to be done on many other gene families, and the claims need to be backed by biochemical experiments.

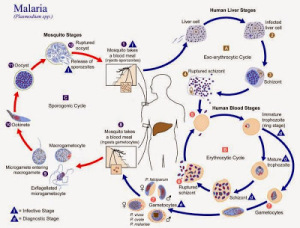

Malaria parasites belong to an ancient lineage that diverged very early from the main branch of eukaryotes. The approximately 90-member plasmodial kinome includes a majority of eukaryotic protein kinases that clearly cluster within the AGC, CMGC, TKL, CaMK and CK1 groups found in yeast, plants and mammals, testifying to the ancient ancestry of these families. However, several hundred millions years of independent evolution, and the specific pressures brought about by first a photosynthetic and then a parasitic lifestyle, led to the emergence of unique features in the plasmodial kinome. These include taxon- restricted kinase families, and unique peculiarities of individual enzymes even when they have homologues in other eukaryotes. Here, we merge essential aspects of all three malaria-related communications that were presented at the Evolution of Protein Phosphorylation meeting, and propose an integrated discussion of the specific features of the parasites kinome and phosphoproteome.

Readers may also enjoy the following informative paper from the same group. It covers Apicomplexa, of which Plasdomium is a member.

Structural and evolutionary divergence of eukaryotic protein kinases in Apicomplexa

Background: The Apicomplexa constitute an evolutionarily divergent phylum of protozoan pathogens responsible

for widespread parasitic diseases such as malaria and toxoplasmosis. Many cellular functions in these medically

important organisms are controlled by protein kinases, which have emerged as promising drug targets for parasitic

diseases. However, an incomplete understanding of how apicomplexan kinases structurally and mechanistically

differ from their host counterparts has hindered drug development efforts to target parasite kinases.

Results: We used the wealth of sequence data recently made available for 15 apicomplexan species to identify the

kinome of each species and quantify the evolutionary constraints imposed on each family of apicomplexan kinases.

Our analysis revealed lineage-specific adaptations in selected families, namely cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK),

calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) and CLK/LAMMER, which have been identified as important in the

pathogenesis of these organisms. Bayesian analysis of selective constraints imposed on these families identified the

sequence and structural features that most distinguish apicomplexan protein kinases from their homologs in

model organisms and other eukaryotes. In particular, in a subfamily of CDKs orthologous to Plasmodium falciparum

crk-5, the activation loop contains a novel PTxC motif which is absent from all CDKs outside Apicomplexa. Our

analysis also suggests a convergent mode of regulation in a subset of apicomplexan CDPKs and mammalian

MAPKs involving a commonly conserved arginine in the aC helix. In all recognized apicomplexan CLKs, we find a

set of co-conserved residues involved in substrate recognition and docking that are distinct from metazoan CLKs.

Conclusions: We pinpoint key conserved residues that can be predicted to mediate functional differences from

eukaryotic homologs in three identified kinase families. We discuss the structural, functional and evolutionary

implications of these lineage-specific variations and propose specific hypotheses for experimental investigation. The

apicomplexan-specific kinase features reported in this study can be used in the design of selective kinase inhibitors.