Challenging Times Ahead for PLOS?

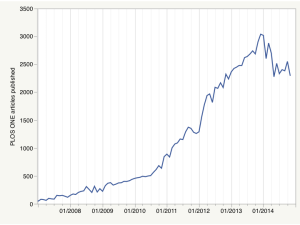

Scholarly kitchen blog posted an interesting chart showing publication output of PLOS One. Apparently, the number of papers dropped 25% in one year from the peak in December 2013. (h/t: @cshperspectives)

PLOS One experienced meteoric growth between 2010 and 2013, and it was well expected that the growth would slow down. However, the rapidity and extent of decline suggest something else is afoot.

-————————————————————————–

They did ring a bell at the top

The timing of the peak itself is curious, because it coincides with the month of Randy Schekman’s appeal to scientists to reject Cell/Nature/Science. Schekman did not mention PLOS One in his letter, but he made a strong case for rejecting journal impact factor and selectivity and promoted a publishing model that should have given PLOS One big boost. That is no coincidence given that he was convinced about the merits of this new publishing model by his colleague and PLOS founder Mike Eisen.

How journals like Nature, Cell and Science are damaging science

These journals aggressively curate their brands, in ways more conducive to selling subscriptions than to stimulating the most important research. Like fashion designers who create limited-edition handbags or suits, they know scarcity stokes demand, so they artificially restrict the number of papers they accept. The exclusive brands are then marketed with a gimmick called “impact factor” a score for each journal, measuring the number of times its papers are cited by subsequent research. Better papers, the theory goes, are cited more often, so better journals boast higher scores. Yet it is a deeply flawed measure, pursuing which has become an end in itself and is as damaging to science as the bonus culture is to banking.

-————————————————————————–

Why this sharp decline?

An endorsement from Nobel Laureate should have given PLOS One a big boost, but instead its publications topped in the same month and declined ahead. To explain why, Scholarly Kitchen blog suggested a number of reasons and we will add one more.

1. Competition

Now that the open-access online publication model gained its acceptance, a large number of competitors of PLOS One have come into the fray. They include -

(ii) Frontiers,

(iii) Nature Reports

(iv) Elife (backed by HHMI),

(v) PeerJ

(vi) GigaScience (backed by BGI).

Moreover, the traditional journals are allowing open-access option and some researchers find that attractive. Finally, if everything else fails, there is always the possibility of placing the preprint in arxiv or biorxiv to make it openly accessible. Traditional closed-access journals are becoming less relaxed about chasing and removing those preprints.

However, competition alone does not explain the rapid drop of PLOS One papers.

2. More restrictive data policy

Scholarly Kitchen blog discussed whether the newly implemented data policy of PLOS journals had any impact and came to the following conclusion.

Based on the graph, the effect of PLOS data sharing policy, implemented in March 2014 does not seem to be driving authors away en masse. However, the policy does not appear to be enforced by the publisher, at least at this time. If the policies were implemented as a requirementwith publication withheld until compliance, as the reviewer form clearly states it may also have an impact on the the journal submission preference of PLOS authors.

3. Funding - stimulus has run its course

The issue of science funding was not discussed in the Scholarly Kitchen article, but could be the most dominant factor. In 2009, US and European scientists received huge boost from post-financial crash stimulus spending. Papers written with that excess funding came into the system in 2011-2013 and many were likely published in PLOS One.

Now that the science funding situation has become more restrictive, it is possible that the total number of papers submitted to PLOS One has also fallen. Moreover, with reduced funding, the researchers have become cautious about publication fee, whereas it was considered an acceptable cost of doing business in the past.

-————————————————————————–

Will PLOS Survive?

PLOS One still receives and publishes a large number of papers, and therefore it is too early to discuss the survival of the organization. However, we like to point out that a number of factors helping PLOS gain its prominence may act like Achilles’ heel during its period of decline and reorganization.

1. Non-profit status

The point of PLOS being organized as non-profit has often been mentioned by Mike Eisen as its distinguishing factor compared to Springer, Wiley and other commercial ventures, but being non-profit has its own drawbacks. Scholarly Kitchen wrote -

Unlike commercial ventures, non-profit organizations are constrained with what they can do with surplus cash and still retain their non-profit tax- exempt status. PLOS has no stockholders who insist on being rewarded with quarterly dividends. PLOS was started with foundation grants, not venture capital from investors, who wait eagerly to cash-in on the spoils of scientific publishing. In 2013, PLOS did what other non-profit publishers in their situation would do with a lot of extra cashthey invested in their organization. According to their financial report, PLOS invested by building infrastructure, hiring more staff and increasing the size of their US and UK offices.

While these investments sound wise, we need to remember that all of this infrastructure is based on a stream of APCs that now appears to be in flux.

2. Lack of character, reputation, ‘impact factor’ or whatever you call it

Most traditional topical journals have their own characters in terms of subjects being covered, and that character is often determined by the vision, interests and reputation of the founding editors. For example, the journal Bioinformatics only covers articles on bioinformatics algorithms, whwreas Biology Direct, one of our favorite journals, contains detailed articles and reviews on various topics related to evolutionary genomics. The later journal was started by Eugene Koonin, Laura Landweber and David J. Lipman, respected biologists working in related areas. Non-topical journals like Nature, Science and Cell, on the other hand, rely on their selectivity and wide readership.

PLOS One went after this second market and branded itself as non-selective, non-topical journal. Moreover, it neutralized the ‘wide readership’ plus point of Nature, Science and Cell with its own ‘open access’ campaign, supposedly implying wide readership due to ease of access.

That worked well, but now that open access has become the mantra of almost all journals, how does PLOS distinguish itself from other burgeoning open-access competitors? There are only three ways for a journal to compete - (i) reputation of editors, (ii) cost and (iii) technology, and among those (ii) and (iii) seem to be the most viable options for PLOS. Competing based on cost of publishing is a dead-end road, and therefore the strongest winning point for PLOS could have been competing in terms of superior technology.

3. Location in California and Chinese Competition

PLOS was founded in 2000, when California, its place of founding, had huge technological lead over other parts of the world. The strategies taken by the journal benefited strongly from that technological advantage. That lead has fallen off and California has now become too expensive for tech-heavy organizations. Gigascience, a journal started by BGI, built GigaDB for submission of large genomic data sets associated with published papers. We expected PLOS to use similar innovative steps to maintain its advantage over competing journals, but the cost of replicating the same is possibly too high in California.

The evolution of PLOS from here onward will be interesting to watch. Why the number of publications fell sharply, whether the decline will continue and what strategies the organization will take to bring down the costs and compete effectively are all important factors to determine its fate. Moreover, if decline of funding is the true cause of fall in published papers, other journals should see impact sooner or later. It seems obvious that the biology space has too many journals and will benefit from a round of ‘creative destruction’ imposed by shortfall in funding.