First Issue of Nature

Few days back, we jokingly recommended researchers to submit their papers to Titus Brown’s blog. However, if you take a look at the first issue of Nature, it will remind you more of a blog than a journal. Being ‘bloggy’ and covering topics considered to be fringe by established scientists of the era allowed Nature to outlast its competition.

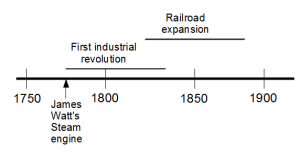

The year was 1869. To put the period in historical context, we have drawn a timeline with two major historical developments. James Watt’s invention of steam engine in 1760s started a technological revolution that dramatically improved quality of life of all Europeans. Confluence of three changes could be seen by mid-19th century. (i) Many people had free time and were curious about science. (ii) Books could be printed in high volume with mechanized printing machines. (iii) Proliferation of railroads, ships and steam-boats ensured delivery of periodicals over a long distance, and thus ensured a large market. Several entrepreneurs realized the potential for new popular science periodicals, and a number of such publications started after 1850. Nature was the last among them.

Nature, first created in 1869, was not the first magazine of its kind in Britain. One journal to precede Nature was titled Recreative Science: A Record and Remembrancer of Intellectual Observation, which, created in 1859, began as a natural history magazine and progressed to include more physical observational science and technical subjects and less natural history. The journal’s name changed from its original title to Intellectual Observer: A Review of Natural History, Microscopic Research, and Recreative Science and then later to the Student and Intellectual Observer of Science, Literature, and Art. While Recreative Science had attempted to include more physical sciences such as astronomy and archaeology, the Intellectual Observer broadened itself further to include literature and art as well. Similar to Recreative Science was the scientific journal titled Popular Science Review, created in 1862,[9] which covered different fields of science by creating subsections titled ‘Scientific Summary’ or ‘Quarterly Retrospect,’ with book reviews and commentary on the latest scientific works and publications. Two other journals produced in England prior to the development of Nature were titled the Quarterly Journal of Science and Scientific Opinion, founded in 1864 and 1868, respectively. The journal most closely related to Nature in its editorship and format was titled The Reader, created in 1864; the publication mixed science with literature and art in an attempt to reach an audience outside of the scientific community, similar to Popular Science Review.

Here is the first issue of Recreative Science, if you like to take a look. All those periodicals folded within 15-20 years, but Nature survived for promoting a non-mainstream idea of the day. It was written by a small group of ‘bloggers’ known as X-club, who were ardent believers of the idea.

Many of the early editions of Nature consisted of articles written by members of a group that called itself the X Club, a group of scientists known for having liberal, progressive, and somewhat controversial scientific beliefs relative to the time period.

What was that non-mainstream idea?

These scientists were all avid supporters of Darwin’s theory of evolution as common descent, a theory which, during the latter-half of the 19th century, received a great deal of criticism among more conservative groups of scientists. Perhaps it was in part its scientific liberality that made Nature a longer-lasting success than its predecessors. John Maddox, editor of Nature from 1966 to 1973 as well as from 1980 to 1995, suggested at a celebratory dinner for the journal’s centennial edition that perhaps it was the journalistic qualities of Nature that drew readers in; “journalism” Maddox states, “is a way of creating a sense of community among people who would otherwise be isolated from each other. This is what Lockyer’s journal did from the start.”

Journal Science, on the other hand, had everything going right for it from the first day.

Science was founded by New York journalist John Michaels in 1880 with financial support from Thomas Edison and later from Alexander Graham Bell.

…and the result was horrendous.

However, the magazine never gained enough subscribers to succeed and ended publication in March 1882. Entomologist Samuel H. Scudder resurrected the journal one year later and had some success while covering the meetings of prominent American scientific societies, including the AAAS. However, by 1894, Science was again in financial difficulty and was sold to psychologist James McKeen Cattell for $500.

From that point onward, history of Science was tied to AAAS, who made it their official publication.

In an agreement worked out by Cattell and AAAS secretary Leland O. Howard, Science became the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1900.

Where did Einstein publish his papers? He published in German journals Annalen der Physik and Physikalische Zeitschrift. All German language journals like Chemische Berichte, Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift and Klinische Jahrbcher were very important during late 19th and early 20th century, until central bankers stuffed the country with debt and destroyed it with WW I. This time, that fate will be seen by Anglo-Saxon countries in not-too-distant future.

Which scientific journal of today will be significant 150 years later?