A Few Useful Links on Khazar History for Population Biologists

We have been interested in history and especially economic history for many years. The curiosity began, when we were doing research on a debt-deflation related commentary and came across an online article titled How Venice Rigged The First, and Worst, Global Financial Collapse.

When you read historical commentaries like above, do keep in mind that you cannot trust anything written by historians unless you do your own analysis, and even after that, you should not trust yourself. It is very difficult to do objective analysis of history. Many commentators (aka historians/social ‘scientists’) do not respect ‘correlation is not causation’, and infer causality, when there is none. Check Paul Krugman’s ‘WW II ended great depression’ narration for example. If you read the history of panic of 1857 and following economic depression, you will find that no ‘new deal’ was tried for that depression, but depression ended naturally in 1859 and US civil war started within a year. Could it be that wars tend to start at the ends of major economic depressions, because social mood is at its lowest? Do not expect Krugman to point out inconvenient facts challenging his favorite hypothesis or alternate explanations.

Over time, we learned that it is nearly impossible to explain financial details of any historical event with certainty, but with plenty of information, it is possible to find holes in bad theories. Therefore, a small group of us communicate over internet to discuss financial and historical developments over the last 2600 years to see whether there is any common pattern. We do not work for government grants, and therefore have no motivation to be intellectually dishonest. Intellectual dishonesty is a major problem in most published economic research. For us, the first task was to get the historical order of events correct, and it is in that context, we came across Khazar history. Population biologists interested in analyzing Jewish genotype data may find the following links useful.

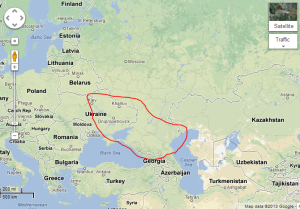

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b7/Khazar_map1.PNG

The suggested location of powerful Khazar kingdom is shown above. Historians try to answer three questions.

(i) Whether a powerful kingdom formed by Turkish tribes existed in that part of the world in 9th century.

(ii) Whether the people or rulers of the kingdom converted to Judaism to maintain good relations with Christian and Muslim neighbors.

(iii) Whether those Turkish tribes migrated westward after dissolution of Khazar kingdom to form the core group of Ashkenazi Jews of today.

We do not have answer to any of those question, but if the topic interests you, please check further in the following links. If you can ignore the political nonsense, this topic may be one of few open problems in human population genetics with very rich reward related to medical discoveries.

1. Thomas S Noonan’s papers:

Historian Thomas Noonan worked extensively on the history of Khazar Khagnate.

Thomas Schaub Noonan (January 20, 1938 June 15, 2001) was an American historian, Slavicist and anthropologist who specialized in early Russian history and Eurasian nomad cultures.

Educated at Indiana University, Noonan was, for many years, a Professor of History at the University of Minnesota. He was the author of dozens of books and articles and one of the leading authorities on the development of the Kievan Rus and the Khazar Khaganate. Noonan placed a great deal of importance on numismatics in understanding economic and social trends. He was the mentor of numerous scholars and leading historians. In 2001 many of his colleagues honored him by publishing the first of a multivolume collection of articles under the title “Festschrift in Honor of Thomas S. Noonan,” which was edited by Roman K. Kovalev and Heidi M. Sherman. The second volume appeared in 2005.

We have been trying to get hold of his papers, but most of them are behind paywalls and not generally accessible. We could only find one that presented numismatics evidence about monetary history of Khazaria. We will be grateful, if readers come across pdfs of any other article and mail us. Here is the list from wiki -

Kievan Rus and early Russia

Noonan, Thomas S. The Nature of Medieval Russian-Estonian Relations, 850-1015 (1974).

Noonan, Thomas S. Medieval Russia, the Mongols, and the West: Novgorod’s relations with the Baltic, 1100-1350 (1975).

Noonan, Thomas S. Fifty Years of Soviet Scholarship on Kievan History: A Recent Soviet Assessment (1980).

Noonan, Thomas S. The Circulation of Byzantine Coins in Kievan Rus (1980).

Noonan, Thomas S. “Russia’s Eastern Trade, 1150-1350: The Archaeological Evidence.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 3 (1983): 201-264.

Noonan, Thomas Schaub. “When Did Rus/Rus’ Merchants First Visit Khazaria and Baghdad?” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 7 (19871991): 213-219.

Noonan, Thomas S. The Islamic World, Russia and the Vikings. Variorium, 1998.

Khazar studies

Noonan, Thomas S. “Did the Khazars Possess a Monetary Economy? An Analysis of the Numismatic Evidence.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 2 (1982): 219-267.

Noonan, Thomas S. “What Does Historical Numismatics Suggest About the History of Khazaria in the Ninth Century?” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 3 (1983): 265-281.

Noonan, Thomas S. “Why Dirhams First Reached Russia: The Role of Arab-Khazar Relations in the Development of the Earliest Islamic Trade with Eastern Europe.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 4 (1984): 151-282.

Noonan, Thomas S. “Khazaria as an Intermediary between Islam and Eastern Europe in the Second Half of the Ninth Century: The Numismatic Perspective.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 5 (1985): 179-204.

Noonan, Thomas S. “Byzantium and the Khazars: a special relationship?” Byzantine Diplomacy: Papers from the Twenty-fourth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Cambridge, March 1990, ed. Jonathan Shepard and Simon Franklin, pp. 109132. Aldershot, England: Variorium, 1992.

Noonan, Thomas S. “What Can Archaeology Tell Us About the Economy of Khazaria?” The Archaeology of the Steppes: Methods and Strategies - Papers from the International Symposium held in Naples 912 November 1992, ed. Bruno Genito, pp. 331345. Napoli, Italy: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1994.

Noonan, Thomas S. “The Khazar Economy.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 9 (19951997): 253-318.

Noonan, Thomas S. “The Khazar-Byzantine World of the Crimea in the Early Middle Ages: The Religious Dimension.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 10 (19981999): 207-230.

Noonan, Thomas S. “Les Khazars et le commerce oriental.” Les changes au Moyen Age: Justinien, Mahomet, Charlemagne: trois empires dans l’conomie mdivale, pp. 8285. Dijon: Editions Faton S.A., 2000.

Noonan, Thomas S. “The Khazar Qaghanate and its Impact on the Early Rus’ State: The translatio imperii from Itil to Kiev.” Nomads in the Sedentary World, eds. Anatoly Khazanov and Andr Wink, pp. 76102. Richmond, England: Curzon Press, 2001.

2. Radhanite merchants

The Radhanites (also Radanites, Hebrew sing. ????? Radhani, pl. ?????? Radhanim; Arabic ??????? ar-Raaniyya) were medieval Jewish merchants. Whether the term, which is used by only a limited number of primary sources, refers to a specific guild, or a clan, or is a generic term for Jewish merchants in the trans-Eurasian trade network is unclear. Jewish merchants were involved in trade between the Christian and Islamic worlds during the early Middle Ages (approx. 5001000). Many trade routes previously established under the Roman Empire continued to function during that period largely through their efforts. Their trade network covered much of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and parts of India and China.

Why are the Radhanites relevant? It is because their activities were detailed in Ibn Khordadbeh’s historical text written in 9th century. Original text from 9th-13th century is possibly the most trustworthy source about activities of Khazar rulers.

These merchants speak Arabic, Persian, Roman,[5] the Frank,[6] Spanish, and Slav languages. They journey from West to East, from East to West, partly on land, partly by sea. They transport from the West eunuchs, female slaves, boys, brocade, castor, marten and other furs, and swords. They take ship from Firanja (France[7]), on the Western Sea, and make for Farama (Pelusium). There they load their goods on camel-back and go by land to al-Kolzum (Suez), a distance of twenty-five farsakhs (parasangs). They embark in the East Sea and sail from al-Kolzum to al-Jar (port of Medina) and al-Jeddah, then they go to Sind, India, and China. On their return from China they carry back musk, aloes, camphor, cinnamon, and other products of the Eastern countries to al- Kolzum and bring them back to Farama, where they again embark on the Western Sea. Some make sail for Constantinople to sell their goods to the Romans; others go to the palace of the King of the Franks to place their goods. Sometimes these Jew merchants, when embarking from the land of the Franks, on the Western Sea, make for Antioch (at the head of the Orontes River); thence by land to al-Jabia (al-Hanaya on the bank of the Euphrates), where they arrive after three days march. There they embark on the Euphrates and reach Baghdad, whence they sail down the Tigris, to al-Obolla. From al-Obolla they sail for Oman, Sindh, Hind, and China.

Few other points on Radhanites from the wiki:

-

Some [historians] believe that Jewish merchants such as the Radhanites were instrumental in bringing paper-making west.

-

Joseph of Spain, possibly a Radhanite, is credited by some sources with introducing the so-called Hindu-Arabic numerals from India to Europe.

-

Historically, Jewish communities used letters of credit to transport large quantities of money without the risk of theft from at least classical times. This system was developed and put into force on an unprecedented scale by medieval Jewish merchants such as the Radhanites; if so, they may be counted among the precursors to the banks that arose during the late Middle Ages and early modern period.

-

Some scholars believe that the Radhanites may have played a role in the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism.

-

In addition, they may have helped establish Jewish communities at various points along their trade routes, and were probably involved in the early Jewish settlement of Eastern Europe, Central Asia, China and India.

Moreover, every once in a while archaeologists discover old documents possibly carried by those traders, which may lead us to additional information about them and Khazars.

Scrolls raise questions as to Afghan Jewish history

An Afghan shepherd enters a wolves den perched high in the mountains of Samangan province looking for a sheep that went astray.

…

Prof. Robert Eisenman, a noted scholar of the Dead Sea Scrolls, hopes such findings might shed light on the Rhadanites, a group of early medieval Jewish merchants who set up an expansive trade network that connected Europe and Asia. He said the Jewish community that penned the documents found in Afghanistan might be a left over of the Rhadanites, which had mostly disappeared by the 11th century. Moreover, he said such discoveries might teach us about the historical origins of peoples in Central Asia.

3. Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk

The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk or Pacts and Constitutions of Rights and Freedoms of the Zaporizhian Host was a 1710 constitutional document written by Hetman Pylyp Orlyk. It established a democratic standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws. The Constitution also limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council. Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution was unique for its historic period, and was one of the first state constitutions in Europe.

Although the above 1710 constitution is not a source of historical information on Khazars, it may be instructive to check other documents from 16th or 17th century to learn why the constitution claimed Khazar origin of Cossacks.

4. Khazaria.com

The website hosts tons of information including some text from the book ‘The Jews of Khazaria’ by Kevin Alan Brook.

The Jews of Khazaria recounts the eventful history of the Turkic kingdom of Khazaria, which was located in eastern Europe and flourished as an independent state from about 650 to 1016. As a major world power, Khazaria enjoyed diplomatic and trade relations with many peoples and nations (including the Byzantines, Alans, Magyars, and Slavs) and changed the course of medieval history in many ways. Did you know that if not for the Khazars, much of eastern Europe would have been overrun by the Arabs and become Islamic? In the same way as Charles Martel and his Franks stopped the advance of Muslims at the Battle of Poitiers in the West, the Khazars blunted the northward advance of the Arabs that was surging across the Caucasus in the 8th century.

The Khazar people belonged to a grouping of Turks who wrote in a runic script that originated in Mongolia. The royalty of the Khazar kingdom was descended from the Ashina Turkic dynasty. In the ninth century, the Khazarian royalty and nobility as well as a significant portion of the Khazarian Turkic population embraced the Jewish religion. After their conversion, the Khazars were ruled by a succession of Jewish kings and began to adopt the hallmarks of Jewish civilization, including the Torah and Talmud, the Hebrew script, and the observance of Jewish holidays. A portion of the empire’s population adopted Christianity and Islam.

This volume traces the development of the Khazars from their early beginnings as a tribe to the decline and fall of their kingdom. It demonstrates that Khazaria had manufacturing industries, trade routes, an organized judicial system, and a diverse population. It also examines the many migrations of the Khazar people into Hungary, Ukraine, and other areas of Europe and their subsequent assimilation, providing the most comprehensive treatment of this complex issue to date. The final chapter enumerates the Jewish communities of eastern Europe which sprung up after the fall of Khazaria and proposes that the Jews from the former Russian Empire are descended from a mixture of Khazar Jews, German Jews, Greek Jews, and Slavs.

5. Douglas Morton Dunlop

wiki:

Born in England, Dunlop studied at Bonn and Oxford under the historian Paul Ernst Kahle (18751965). His work was also influenced by such scholars as Zeki Validi Togan, Mikhail Artamonov, and George Vernadsky.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Dunlop was Professor of History at Columbia University in New York. He is best known for his influential histories of Arab civilization and the Khazar Khaganate. Dunlop was the “most esteemed scholar of the Khazar monarchy.” He had command of the many languages needed to study the Khazars, information about whom is found in Arabic, Byzantine, Hebrew and Chinese literature.

His books:

The History of the Jewish Khazars, New York: Schocken Books, 1967.

“The Khazars.” The Dark Ages: Jews in Christian Europe, 7111096. 1966.

Last but not the least,

6. The Thirteenth Tribe by Arthur Koestler

We found a freely available copy from this website.

Arthur Koestler lived quite an unusual life and left the world through an unusual death.

The Thirteenth Tribe (1976) is a book by Arthur Koestler, which advances the thesis that Ashkenazi Jews are not descended from the historical Israelites of antiquity, but from Khazars, a Turkic people. Koestler’s hypothesis is that the Khazars converted to Judaism in the 8th century, and migrated westwards into Eastern Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries when the Khazar Empire was collapsing.

Koestler used previous works by Abraham Poliak, Raphael Patai and Douglas Morton Dunlop as sources. His stated intent was to make antisemitism disappear by disproving its racial basis.