'Epigenetics' Explained, in the Context of Descendants of Holocaust and Slavery Victims

A renowned psychologist asked us by email:

It has been posited that the trauma involved in genocide has altered gene expression not only of Holocaust survivors (as well as descendents of African slaves and conquered Native American) but of their descendents. is there any theoretical or empirical basis for that proposal?

We are posting the response here in case others come across the same claim. Please feel free to point out any error or disagreement in the comment section.

Our response:

In 2010, Drs. Davidson, Hobert and Ptashne published a letter in Nature titled “Questions over the scientific basis of epigenome project”. In addition, Dr. Mark Ptashne published two articles -

Faddish Stuff: Epigenetics and the Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics

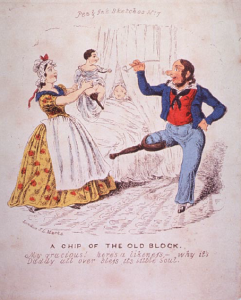

(The above image from the paper is a beautiful illustration of idiocy behind the concept of epigenetics and inheritance of acquired characteristics.)

You will find those articles helpful regarding your question. Needless to add, Professors Davidson, Hobert and Ptashne are all highly respected researchers in genetics.

To give very brief answer to your question - “are there any theoretical or empirical basis for that proposal?” - no, definitely not in humans or any organism remotely similar to humans. I sent Dr. Hobert your question and he also said - “Allow me to add that the claim that you cite is idiotic IF its put in the context of histone modifications.”

Here is the long reply.

The word ‘epigenetics’ was introduced by biologist C. H. Waddington in

1940s to explain how the cells maintained their states during development.

For example, the muscle cells, once differentiated, continue to divide into muscle cells and the same is true for other kinds of cells, even though they all start from one universal mother cell and carry the same chromosomes after division. How does a cell get programmed into being a muscle cell or neuronal cell? Waddington speculated that there must be some ‘epigenetic’ effect, because all cells continue to have the same chromosomes and therefore the same set of genes.

Please note that in 1942, there was no DNA sequence and Waddington was trying to explain things in abstract terms. In the following 60+ years, Waddington’s question was fully answered by geneticists and developmental biologists. It is found that the cells remember their states (muscle or neuron or kidney, etc.) through the actions of a set of genes called transcription factors acting on other genes through binding sites on the chromosomes. Both Professor Ptashne and Professor Davidson’s labs did extensive research to elucidate the mechanisms, and Waddington’s ‘epigenetics’ was explained through their work.

In the meanwhile, a group of scientists hijacked the term ‘epigenetic’, started to make unsubstantiated claims about DNA methylation and histone modifications and convinced NIH to give them large pots of money. The bad claims on ‘epigenetic’ effects you cited are due to their work and I think you will find Ptashne’s linked paper informative in that regard.

Regarding your question -

“It has been posited that the trauma involved in genocide has altered gene expression not only of Holocaust survivors (as well as descendents of African slaves and conquered Native American) but of their descendents. is there any theoretical or empirical basis for that proposal?”

I am always open to any new idea, but when I try to confirm such claims by reading the primary documents, I notice several problems -

(i) The memory mechanism (DNA methylation, histone modification) suggested in the epigenetics papers cannot be transferred from cell to cell. So, even if I entertain the idea that one cell or one group of cells got harmed due to stress, that effect is supposed to go away after the cell(s) divides,

(ii) The above issue becomes even more critical, when one tries to make a multi-generational claim. In one’s body, only a small fraction of cells (germ cells) can carry information to the children. Therefore, there has to be a mechanism for the ‘epigenetic stress due to histone modification’ to be transfered to germ cells in order to be transmitted to the next generation. I do not know of any mechanism given that histone methylation itself does not get carried from cell to cell.

(iii) Since I am bothered by such basic issues, I try to check the details of the experiments making bold claims related to epigenetics and there I find another problem. Usually the experiments tend to be very data poor. Typical genome-wide association study experiments are performed on thousands of individuals and even after that the researchers claim that they have difficulty finding genetic basis of complex diseases. In that context, using 20 or 30 mice to make a bold claim on ‘epigenetics’ is laughable.

That brings us to the broader question - is stress-induced multi-generation effect ever seen in anywhere in nature? That is where Dr. Hobert’s lab comes in. They shown starvation-induced trans-generational inheritance in worms -

Starvation-Induced Transgenerational Inheritance of Small RNAs in C. elegans

The mechanism, however, is not methylation or histone acetylation, but is something completely different (small RNA). Nothing like this has been demonstrated in humans, and given the genetic distance between worms and humans, I would like to see real evidence before accepting such a mechanism being in action in humans.

-————————-

For our readers’ convenience, we reproduce the letter to Nature by Davidson, Hobert and Ptashne, because we had difficulty finding it for a while.

Questions over the scientific basis of epigenome project

We were astonished to see two sentences in your Editorial on the International Human Epigenome Consortium (Nature 463, 587; 2010) that seem to disregard principles of gene regulation and of evolutionary and developmental biology that have been established during the past 50 years.

You say: By 2004, largescale genome projects were already indicating that genome sequences, within and across species, were too similar to be able to explain the diversity of life. It was instead clear that epigenetics those changes to gene expression caused by chemical modification of DNA and its associated proteins could explain much about how these similar genetic codes are expressed uniquely in different cells, in different environmental conditions and at different times.

With respect to epigenomics, we wish to stress that chromatin marks and local chemical modifications of DNA, such as methylation, are the

consequences of DNA-sequence-specific interactions of proteins

(and RNA) that recruit modifying enzymes to specific targets. They are thus directly dependent on the genomic sequence. Such marks are the effects of sequence-specific regulatory interactions, not the causes of cell-type- specific gene expression. Gene regulation explains in outline, and in many cases in detail, how similar genomes give rise to different organisms. Self- maintaining loops of regulatory gene expression are switched on and off, producing the epigenetic effects that lie at them heart of development. Whereas the protein-coding toolkit is in part similar among species, the remainder of the genome,

including almost all the regulatory sequence, is unique to each clade:

therein lies the explanation for the diversity of animal life.

A letter signed by eight prominent scientists (not including us), and an associated petition signed by more than 50, went into these matters in greater detail, and expressed serious reservations about the scientific basis of the epigenome project. A modified version of the letter appeared in Science (H. D. Madhani et al. Science 322, 4344;

2008) the complete letter can be found at http://madhanilab.ucsf.edu/epigenomics.