Where Does the Genetic Code Come From? (Twelve Fundamental Problems for Bioinformatics)

A few months back, in a series of three posts, we urged bioinformaticians and computational biologists (they mean same thing) to think about the fundamental problems in biology, and then build tools to take advantage of massive next-generation sequencing data sets to solve those fundamental problems.

Bioinformatics at a Crossroad Again Which Way Next?

Crossroads (ii) Is It Too Late to Acknowledge that Systems Biology and GWAS Failed?

Crossroads (iii) a New Direction for Bioinformatics with Twelve Fundamental Problems

i) Prokaryote-eukaryotic discontinuity

ii) Evolution of eukaryotic cilia

iii) Origin of life RNA world

iv) Origin of sex in eukaryotes

v) Neuro-muscular junction and role of electricity

vi) Flexibility of genome

vii) Animal body plan

viii) Evolution of receptors

ix) Death and Aging

x) Evolution of immune systems in eukaryotes

xi) Evolution of Metabolic Network and Photosynthesis

xii) Brain, intelligence, Consciousness (and maybe Eusociality in bees/ants)

To initiate the effort, we listed the above twelve fundamental problems and wrote several blog posts to link to relevant papers on those topics. Many of those posts can be found in our ‘evolution and ncRNA’ section, which happens to be the least visited one !

On the third problem, Mike White posted an interview with Dr. Charles Carter in Finch and Pea blog that our readers will find informative. The first part is online and we will link to the second part, when it appears. Readers may also take a look at ‘The Most Difficult Problem in Computational Biology’ to find other relevant papers.

Where Does the Genetic Code Come From? An Interview with Dr. Charles Carter, Part I.

The genetic code is one of biologys few universals*, but rather than being the result of some deep underlying logic, its often said to be a frozen accident the outcome of evolutionary chance, something that easily could have turned out another way. This idea, though its often repeated, has been challenged for decades. The accumulated evidence shows that the genetic code isnt as arbitrary as we might naively think. And more importantly, this evidence also offers some tantalizing clues to how the genetic code came to be.

This origins of the genetic code has long been a research focus of University of North Carolina biophysicist Charles Carter, and his UNC enzymologist colleague Richard Wolfenden. They authored a pair of recent papers that suggest behind the genetic code are actually two codes, reflecting key steps in its evolution. Dr. Carter kindly agreed to answer some questions about the papers, which present some interesting results that add to the growing pile of evidence that the genetic code is much less accidental that it may seem.

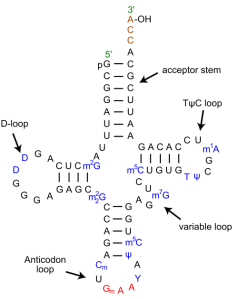

These papers deal with the machinery that implements the genetic code. Conceptually the code is simple: it is a set of dictionary entries or key- value pairs mapping codons to amino acids. But to make this mapping happen physically, you need, as Francis Crick correctly hypothesized back in 1958, an adapter. That adapter, as most of our readers know, is tRNA, a nucleic acid molecule that is charged with an amino acid.

But the existence of tRNAs creates another coding problem: how does the right tRNA get paired with the correct amino acid? The answer to this question is at the heart of the origin of the genetic code, and its the subject of these two recent papers. More about this story, as well as the first part of my interview with Dr. Carter, is below the fold.

So how do you get the correct codon/amino acid pairings on a tRNA? This, as youll remember from your biochemistry courses, is accomplished through a set of enzymes called tRNA synthetases that charge the tRNAs with their corresponding amino acid. tRNA synthetases are central to the secret of how the genetic code evolved. As Dr. Carter noted in a piece about Thawing the Frozen Accident’, The emergence of the genetic code was inseparable from the ancestry of the RNA adaptors and protein catalysts that implement it now. Hes been interested in exactly that problem how early RNAs and protein catalysts developed into the universal coding system we have today.

The striking result in the recent work by Carter and Wolfenden has to do with how tRNAs are recognized by certain tRNA synthetases. Their results indicate that tRNAs carry two codes: the well-known one in the anti-codon (the part that directly matches genetic code codons), and a second one in the acceptor stem. (See the figure below.)

Continue reading here and part II is posted here.

Last week we discussed the general question of how the genetic code evolved, and noted that the idea of the code as merely a frozen accident an almost completely arbitrary key/value pairing of codons and amino acids is not consistent with the evidence that has been amassed over the past three decades. Instead, there are deeper patterns in the code that go beyond the obvious redundancy of synonymous codons. These patterns give us important clues about the evolutionary steps that led to the genetic code that was present in the last universal common ancestor of all present-day life.