Nature Journal Recognizes arXiv.org (or its own Wile E. Coyote Moment)

A column in Nature News comments on the recent surge in acceptance of arXiv.org among the geneticists. We wonder why it took the biology community so long to embrace truly open publishing.

The website arxiv.org was developed in 1991 by Cornell theoretical physicist Paul Ginsparg, who started it as a small unfunded project in addition to his own research. The side activity became so popular among physicists that, around mid-90s, US government decided to fund Ginsparg to develop it further.

We came to learn about arxiv.org in 1995-1996 as young graduate students working on condensed matter physics. Convincing our professor to put unpublished papers in a ‘fringe’ website was indeed a hard sell. We tried all possible arguments (‘increasing visibility’, ‘you get cited, not scooped’ etc.) without success. Finally, a friendly article in Physics Today and NSF’s decision to fund the project to bring it mainstream changed his mind.

Why is arxiv.org so successful? It is simply because the preprint server is swimming with the tide. Let us explain.

The word ‘publish’ means presenting something to the public. In a long gone era, Martin Luther ‘published’ his ninety five theses by nailing them on the door of Castle Church of Wittenberg. In the same vain, if all geneticists of the world lived in a small town on California coast and went to the same coffee shop every day, posting a research article on its bulletin board would have been enough evidence of publication of a discovery.

Our world is far more complex leading to modern norms of publication in well- circulated journals. Historically, established journals like Nature and Science started between 1860-1880, when industrial revolution allowed mass production and circulation of popular magazines, newspapers and scientific journals. With increasing interest in science among people, many other journals were created afterward to cover topics of special interest.

From the advent of industrial revolution to mid-1990s, scientists had only two inexpensive ways to reach wide audience - (i) oral presentation at a conference, (ii) publication in a journal. Among those two, the words spoken in oral presentations could be ‘changed on a dime’. Moreover, those words were not accessible to scientists not attending a specific conference. So, presenting in print media was the only way to make sure the results of research were known to public or were ‘published’.

All that changed with the arrival of internet. Internet allows global dissemination of research results at a fraction of cost compared to print media. Moreover, internet has many advantages that the print media cannot replicate. For example, scientists can communicate through mailing lists, blogs, github and even twitter. Do we really need the print media?

To explain how effective the internet is in disseminating scientific information, the authors of Velvet assembler wrote another program named Oases for transcriptome assembly. The program is freely available from public repository and has been used by hundreds of researchers. From that viewpoint, the program was published on the very day it was uploaded to github. It is being further developed by an active community of bioinformaticians, who keep in touch through a mailing list. The above process built stronger credibility for Oases than its eventual ‘publication’ in a print journal. Similarly, UCSC genome browser is a different form of publication, and users learn about it by using the website, not by reading about it in paper published in print journal.

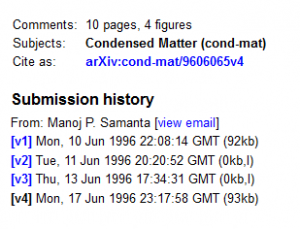

Print journals continue to claim relevance by giving clear time-stamp to papers, and that is where the beauty of arxiv.org is seen. A paper uploaded to arxiv.org also gets a specific time-stamp. The paper can be edited further, and various edits are kept separately. You can see an example here from one of our earlier publications in 1996. The paper was updated four times and arxiv.org preserved all its history.

One line of criticism often made against arxiv.org in the early days turned out to be baseless. It was the issue of lack of editors and reviewers for the e-journal. Arxiv.org has a process of self-selection, by which the community ‘accepts’ good papers by citing them more and ‘rejects’ bad papers by ignoring them. Eventually, PLOS One followed similar model, but arxiv.org came at the right price ($0.000) compared to PLOS One ($1000). Still, both are well ahead of the Nature journal, which charges a reader $32 to let them read only the Trinity paper.

If the above trend of publishing in preprint servers take hold, it will destroy the business model of print biology journals with high cost of access. Why will a smart researcher pay premium price to a journal, when his paper collects all citations based on its arxiv.org postings? Moreover, we anticipate that medical research community will experience significant cuts in funding in the coming years, and will fully embrace arxiv.org, just like the physicists did in early 90s after governments dramatically reduced funding for nuclear research.

-————————————–

Relevant links -