Cleverness of the Ray Assembler

Reader Mikael Huss, who writes the informative Follow the Data blog, asked us about how Ray and ABySS parallelize and speed up genome assembly. After few back and forth email exchanges, we realized that Ray is liked for two reasons - (i) distributed MPI-based assembly, (ii) longer contigs than many other assemblers (such as Velvet). We will discuss the second point here, and talk about parallel assembly in a follow up commentary.

Removing tips and bubbles

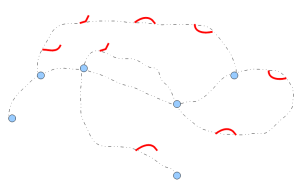

The first few assembly steps have become nearly the same for almost all de Bruijn graph-based assemblers. They all split the reads into k-mers, combine k-mers into de Bruijn graph and resolve the graph into contigs. At first the graph looks like following figure, where each dotted line is made of many k-mers.

The red lines (tips and bubbles) in the above graph are likely from sequencing errors and need to be cleaned before the assembly can be further continued. All de Bruijn graph-based assemblers have procedures for removing tips and bubbles.

Contig assembly

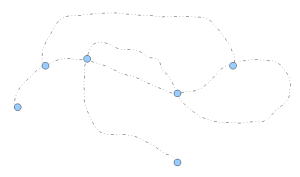

After the clean-up step, the de Bruijn graph looks like the following figure:

The contigs coming out of assemblers are genomic regions covered by the nodes between pairs of connected blue circles. Those regions can be determined unambiguously from the graph structure.

Shortcoming of de Bruijn Graphs

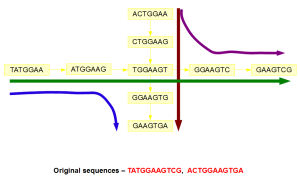

Construction of de Bruijn graph leads to loss of information as shown in the following figure. The original reads cannot be derived from the graph structure, because two spurious paths are generated. Increasing k-mer size is one way to resolve those spurious paths, but increasing k-mer size leads to insufficient coverage in other genomic regions.

Various assembly programs differ in how they handle those two follow up steps after contig assembly -

(i) taking care of the inherent shortcoming of de Bruijn graphs,

(ii) using information from paired end and mate pair reads to join contigs further.

We provide short description of methods used by various assemblers before discussing Ray.

Velvet: Velvet does not have a way to handle the shortcoming of de Bruijn graph construction. Users run it for different values of parameter k and choose the best assembly. Scaffolding of Velvet is error-prone in our experience. The coverage cutoff parameter of Velvet is too drastic, because it does not account for the fact that various regions of a large genome can have different coverage depths.

Minia: Minia is a contig assembler, but by keeping memory usage low, it allows investigation of multiple k-values. Make sure you have a humongous disk before trying assembly at too many k-values in parallel.

ABySS: In our understanding, initial implementation of ABySS had the same handicaps as Velvet, but Shaun Jackman later improved the scaffolding step.

SOAPdenovo2: SOAPdenovo2 does the scaffolding well by keeping all contigs including the smallest ones. Then it hierarchically builds the scaffolds from them by first considering the PE reads, then the shorter mate pairs and finally the longest mate pairs. We do not believe it takes care of multi-kmers well, but the hierarchical procedure appears to properly address the other scaffolding issues.

IDBA: IDBA is an elegant algorithm to handle the inherent shortcoming of de Bruijn graphs. It starts by doing assembly at a low k-mer value, and then moves on to higher and higher k-mers only for the regions, where the de Bruijn graph poses ambiguity at low k-mer values. That way, it does not need to redo the entire assembly at every k-mer. Moreover, the above approach helps IDBA avoid regional sparseness, when it goes to very long k-mers. Those regions are already assembled at low k-mer value and no new input is needed.

ALLPATHS-LG: ALLPATHS supposedly takes care of multiple k-mers, and based on description from the paper, it does something similar to IDBA. However, we never studied the code in detail.

SGA: SGA abandons de Bruijn graph altogether. No dBG, no shortcomings from dBG.

SPAdes: SPAdes algorithm combines multi-kmer (conceptually similar to IDBA, but more elegant) and rectangular graph-based scaffolding algorithm (their innovation) to address dBG-shortcomings and scaffolding respectively.

-—————————————

Ray

Finally we can discuss the approach Ray uses to get long contigs.

i) Unlike other de Bruijn graph algorithms, Ray does not stop the contig- building process at the blue nodes. Instead, it uses a set of heuristics to greedily pick one path or another.

ii) Ray keeps track of the reads from which the k-mers came from. Therefore, unlike other de Bruijn graph algorithms, the path information is not lost. This is effectively similar to having very long k-mers even though the graph is built from one k-mer value.

iii) Ray also keeps track of the read pairs from PE reads. Therefore, the sizes of the hypothetical very long k-mers is bigger than the read size itself. Longer the k-mers, less regions of the genome appear like repeats.

One more point - Ray removes all potentially highly repetitive reads from the assembly based on their k-mer frequency. That reduces quite a bit of noise from steps (i), (ii) and (iii).

We do not know how good the mate pair scaffolding algorithm of Ray is, but that part is less important for metagenome assembly.