Peanut Genome Released

We received a press release about “the first peanut genomes sequenced”. The sequencing was done by International Peanut Genome Initiative in collaboration with BGI, and they are releasing two genomes to the public at this peanutbase website. You can access the full press release with all contact information here, but the following part is interesting for researchers curious about peanut science. Plant polyploidy is a fascinating topic and it surely adds complexity to the assembly process.

The peanut grown in fields today is the result of a natural cross between two wild species, Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis that occurred in the north of Argentina between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago. Because its ancestors were two different species, todays peanut is a tetraploid, meaning the species carries two separate genomes which are designated A and B sub-genomes.

To map the peanuts genome structure, IPGI researchers sequenced the two ancestral parents, because together they represent the cultivated peanut. The sequences provide researchers access to 96 percent of all peanut genes in their genomic context, providing the molecular map needed to more quickly breed drought-resistant, disease-resistant, lower-input and higher-yielding varieties. The two ancestor wild species were collected from nature decades ago. One of the ancestral species, A. duranensis, is widespread but the other, A. ipaensis, has only ever been collected from one location, and indeed may now be extinct in the wild. When grappling with the thorny problem of how to understand peanuts complex genome, it was clear that the genomes of the two ancestor species would provide excellent models for the genome of the cultivated peanut: A. duranenis serving as a model for the A sub-genome of the cultivated peanut and A. ipaensis serving as a model for the B sub-genome. Fortunately because of the long-sighted efforts of germplasm collection and conservation, both species were available for study and use by the IPGI.

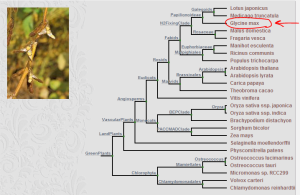

We further looked for plant phylogeny to find where peanut is in the big picture and got warned by wiki - “Despite its name and appearance, the peanut is not a nut, but rather a legume”. Two websites (plaza and phytozome) were helpful in that respect. Borrowing the chart from the plaza website, you should try to fit peanut in the neighborhood of Glycine max (soybean). Bean Phaseolus vulgaris is other relevant organism in this context.

There is very interesting evolutionary history that goes with peanuts and other legumes.

The first definitive legumes appear in the fossil record during the Late Paleocene (about 56 Myr ago) and all three traditionally recognized subfamilies of legumes, the caesalpinioids, mimosoids, and papilionoids appear soon afterward, beginning around 50-55 Ma (Lavin et al., 2005).

Well, the earliest fossil record of primates came from the same time - 55 million years ago. So, possibly it is not a surprise that -

Many Faboideae species are important to humans and include a number of our basic food and fodder plants such as soybeans, garden peas, broad beans, clover and lucerne. Their food value results from high levels of nutrients, especially protein, contained in many species. Most Faboideae have a symbiotic association with bacteria, Rhizobium, which form nodules on the roots. These nodules fix atmospheric nitrogen into a form that is available to plants, making Faboideae important members of both agricultural and ecological communities. Some species (e.g.clovers, medics and lucerne) are grown as cover crops or green manures, to enrich the soil.

Needless to say, genome is only the first step in understanding the complex biology of any organism. We googled ‘peanut genetics’ and found a grand total of two papers on the front page !! That means a lot remain to be learned about this organism.