Algorithmic Differences between Oases and Trinity

We mentioned the publication of Oases paper in our earlier commentary. One question (or should we say the only question) in the mind of an user is which one runs better.

That kind of question is both easy and difficult to answer. The easy answer is to set up a few metrics, compare the programs against each other and report the results. Typical metrics for transcriptome assemblers in the minds of bioinformaticians are

(i) how accurately does the assembler reconstruct the true transcriptome from sequencing reads,

(ii) RAM usage,

(iii) time taken to complete the assembly.

The Oases paper reported a comparison on the first metric and we earlier compared RAM and time usage of Oases and Trinity. Please note that our comparison was based on an earlier version of Trinity. The Trinity group reportedly improved their software by incorporating a better k-mer counting module.

Here comes the difficult part in comparing the performances of two programs. A computer program is a packaged presentation of a set of algorithms. At times, one program may have better algorithm than the other one, but its bad packaging makes it appear worse in a superficial comparison of performance metrics. That problem is easy to fix by tweaking the code little bit. Trinity’s k-mer size being set at 25nt is a good example.

On the other hand, if a computer program runs worse than another due to inferior algorithm, that difference is much harder to overcome. A good example is search programs using and not using Burrows Wheeler Transform. Our blog likes to focus on the algorithmic differences between programs, because that is where the real innovations take place.

Do Oases and Trinity have any algorithmic difference? To answer that question, we need to look into the parts that assemble contigs for those two programs. Velvet does the job for Oases and Inchworm does it for Trinity. When we compare two modules, we find that they indeed have some differences in algorithms.

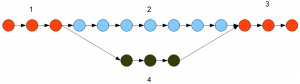

Velvet searches for connectivity in a de Bruijn graph using a depth search module. The search for a contig stops, as soon as a junction is reached in the de Bruijn graph. So, in the example graph presented above, Velvet will identify the branches 1, 2, 3 and 4 as separate contigs. The role of Trinity is to connect all those separate contigs to build the gene structures.

Inchworm is different, because it runs a greedy algorithm that connects as many k-mers as possible without placing any k-mer into two separate contigs. Inchworm does not stop at junctions, but continues forward with assembling contigs. For the graph presented in the above picture, Inchworm will identify 1+2+3 as one contig and 4 as a different contig.

The second difference between Velvet and Inchworm is in their error correction procedure. Inchworm rejects all k-mers with single occurrence in the reads and then starts building contigs with the rest. Velvet has a more sophisticated error correction procedure that removes low occurrence graph structures like tips and bubbles rather than low occurrence k-mers.

We have not thought enough about whether the above differences in algorithms substantially change the number of assembled genes. Superficially, we do not think they matter in the overall assembly, but one can always think of special cases where they do. Especially the practice of rejecting singleton k-mers can help in substantial memory savings, which may explain why Trinity has better memory performance than Velvet.

Based on overall description of algorithms, we expect Trans-ABySS and trans- SOAPdenovo to behave more like Oases than Trinity.

-—————-

P.S.

Question. Which path does Inchworm take at a fork?

Answer. The more traveled one based on the number of reads. If path 1-3 in the above figure has 1000 alternatively spliced representations and path 4 has 200, the read count will vary proportionally. Inchworm will choose 1-3 as the primary path.