Sequester Special - A Bootstrapped Genome Project (i)

About two years back, a long-term collaborator contacted me about an interesting vertebrate organism. His group collected RNA and DNA samples, and he wanted to publish a genome paper in Science or Nature. You know the usual drill. There was only a small problem. They did not have funding to conduct a full scale genome project, or even 1/20th scale genome project (based on Titus Brown’s estimates for the cost of Lamprey genome).

Personally, I do not mind interesting biological problems, but I am highly allergic to genome projects after taking part in 3 or 4 and turning away few others. Traditional genome projects are really boring. Anyone, who runs them for few times runs away from them to remain sane. Just look at J. Craig Venter. You can get a feel for a genome project by going through a typical genome paper, like the ones for rat, dog or beetle. A typical genome paper has the following title and sections -

Title: Genome of organism X provides new insight into biology of X

A. X is an incredibly interesting organism, and sequencing its genome can cure so and so diseases.

B. We sequenced and assembled genome of X, and ran as many comparative bioinformatics packages as we could.

C. We found unusual pattern in a class of genes. Maybe that pattern is linked to the biological behavior of the organism.

Over the last 13 years, genome papers had been the most predictable way to turn X dollars of grant into high visibility journal real estate, and program managers and scientists loved that predictability. Eventually, in 2008, Science and Nature decided not to spend too much of prime real estate on genome papers. However, instead of flat out rejecting genome papers and thus missing media attention of genome release, they increased their total space. How so? They decided to send the old style genome papers to supplementary sections and published short summary of supplement as the main paper.

I do not think genome papers should be published in any journal. Instead the genome and genes should be deposited in a server, and a permalink to that storage should be used for citations. Then the individual scientists can publish their novel biological findings and compete for top journals based on quality of discoveries. In fact, it is even better, if the genome and genes are ‘published’ in sourceforge or github style servers with updates by the minute, as quality of genome changes.

The practice of ‘publishing a genome’ in Science or Nature corrupted biology in several ways, and many things Titus Brown commented about in his Assemblathon review were derivatives of that practice.

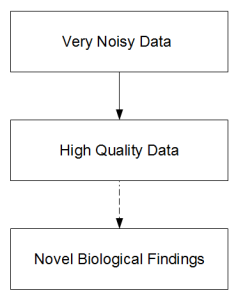

i) The process of sequencing to make biological discoveries has three steps.

The progression from top block to second is an engineering problem, whereas the last part needs unusual insights and is therefore unpredictable. Publication of genome paper with focus of having the genome itself elevates an engineering problem to the status of a scientific discovery. Therefore all kinds of wrong questions tend to get asked. Quality of an engineering solution is judged by cost and achievement. So, if two groups claim to sequence the genome of giraffe, one that does it at 1/10th of cost of other with 1/3rd loss in quality probably did better. When the genome itself is deemed the scientific discovery, better quality at any cost is considered to be good.

ii) Biologists got the wrong impression about quality of genomes, because the media said that ‘THE GENOME’ of chicken was published.

iii) Undue focus on engineering of genome assembly took away money from regular groups and awarded them to genome centers for making big scientific discoveries year after year, even though they were mostly doing engineering.

Getting back to the original topic, I decided to accept the bootstrapped genome project to do things differently. It had been a very rewarding journey over the last two years, and I will share what I learned in the following commentary.