Note: These tutorials are incomplete. More complete versions are being made available for our members. Sign up for free.

Hashing - Basic Concepts

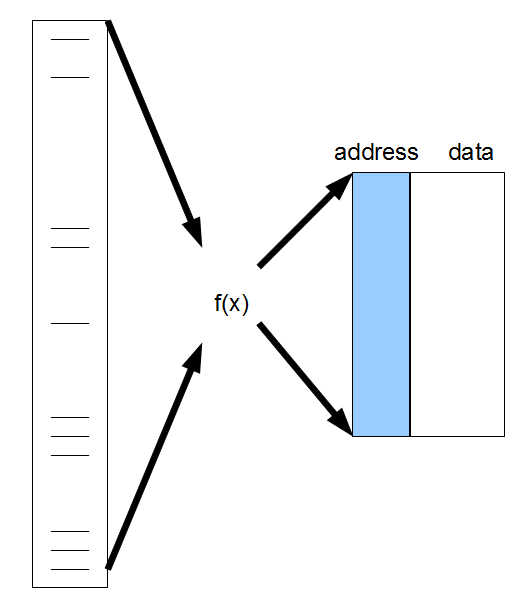

The concept of hashing is lot easier to grasp with some background on computing hardware that without. Hardware allocates linear space. How do we store and access a large number of discontinuous numbers there?

Hash functions are irreversible, but do not need to be reversible, because the entity is stored right inside at the location.

Computation is cheap.

Hash functions

http://www.homolog.us/blogs/blog/2013/04/28/hardware-based-hash-functions/

http://www.homolog.us/blogs/blog/2013/05/06/why-computer-science-professors-dislike-hash-functions/

http://www.homolog.us/blogs/blog/2013/05/07/genome-assembly-programs-what-hash-functions-do-they-use/

EXOR hash

Murmur hash

When is your birthday? (on hashing, sparsehash and murmurhash) Imagine you are giving a talk to a small group of 40 persons, and start with asking everyone his/her birthday. What are the chances that two members in the audience will have the same birthday? The answer is ~90% !! Yes, in 9 out of 10 cases, a small group of 40 people will have at least one pair with common birthday. The answer defies common intuition, but can be proven mathematically. How is asking everyone’s birthday related to NGS bioinformatics? The same kind of question is asked, when we try to design optimal hashing strategy to store data. Suppose you like to save all 21-mers from a small set of reads. You have estimated by some other means that the total number of 21-mers is around 50,000. If you allocate a large array to store all possible 21-mers, that array takes 4^21= 4.4 trillion memory spaces to save only 50,000 entities. The method is inefficient, because a large amount of memory will be wasted. Using hash data structure is a good solution in the above scenario.

How does a hash work? It runs a function (‘hash function’) on each k-mer and converts it into an integer pointing to a location in a table. The size of the table is comparable to the expected number of entities (50,000 in above example), and very little space is wasted. The birthday example can demonstrate well, how hashing works. Let us say you like to store information on all people attending your talk, and want to access it by using the names of people. A data structure with every possible name in the world is wastage of space. So, one possibility is to have a data structure with 366 spots, each representing a day of the year. The data for each person will be stored in the space allocated at his birthday. Asking for each person’s birthday works as the hash function. Real life data like nucleotide sequences do not have birthdays, and need some other kind of hash functions. Designing a good hash function is more art than science. It has to run fast and it has to randomize all input strings within the allocated space. Murmurhash is one of the most efficient hash function at present, and you can check its code at the google link or get some hint here. Based on the birthday example, you can see that collision is the biggest potential problem with hashing. When two persons have the same birthday, they try to reference the same spot in the table and that is a problem. You either need to increase the size of the table, or add extra code to resolve collision. The surprising part is how little the table is filled (only 40 persons out of 366 potential birthdays) before you have substantial chance (~90%) of collision. Google sparsehash is a very efficient open source library that you can use to solve your hashing problems. It is used by NGS assembler ABySS.